Buggy Hardware And Sci-Fi Toys: The Wild Making of Alien vs Predator – Atari’s Last Great Game

When Mike Beaton started working on Alien vs Predator for the Atari Jaguar, he had no idea it would become a cult classic, and that at one point it would lead to staying awake for 72 hours without sleep. As the lead programmer, Beaton pulled off one of the most technically ambitious projects ever seen on a 1990s console, crafting a moody, texture-mapped shooter that helped define Atari’s last stand in the hardware business.

But behind the game’s eerie corridors and Predator vision overlays was a mountain of technical headaches. From uncovering bugs in Jaguar’s custom chips to squeezing performance out of limited memory, Beaton had to work around hardware that was locked in stone by the time development began. Atari wanted a killer game. What they got was a miracle – produced in part from a spare bedroom in Hull.

Now, decades later, Beaton reflects on the improvisation, the pressure, and the philosophy behind AvP’s legacy. He credits the success not to budget or planning, but to the sheer coincidence of the right people coming together at the right moment – when Atari needed them most.

What were you working on before you became the lead programmer on AvP?

I had just finished a game called ATAC for Argonaut Software and I was looking around for the next project. I spoke with a few computer agents at the time, and back then if your agent knew people at other companies they would know who needed programmers. So they knew Rebellion had a chance of working with Atari and needed a 3D programmer. We went together to this initial meeting with Atari and Atari were sitting there kind of showing us their hardware, and most of the companies there I would say were maybe trying to get started or trying to move from a smaller league to a bigger league, by putting forward proposals for Jaguar games. Atari were kind of lucky to get any good games on that basis.

Is it true that AvP was, for its time, so advanced that it actually pushed the boundaries of what the Atari Jaguar could do? Did the game push beyond its limits?

When John Matheson and Martin Brennan, who designed the Jaguar hardware, came to Rebellion to see the early demo with the 3D texture maps, they basically said it was the first thing they’d seen the Jaguar do that they didn’t realize it could do. So that was quite a compliment.

I heard that there was kind of a “marriage” between Atari and AvP and that they were pushing each other along in terms of performance.

There’s some misinformation there. The Jaguar hardware was fixed by the time we got to it. There was no further: ‘oh, we’re going to change this, and we’re going to change that.’ Maybe that was a mistake by Atari. They kind of got the hardware to a state where they thought they were happy with it, and only then went to the games companies. They’d have been better off investing some money into getting some highly reputable, well-known games companies involved and speaking to the hardware designers first, but they didn’t do that.

So the hardware was already in place, and there was no pushing each other along, so to speak, and there were no bugs in the hardware?

No, there were bugs in the hardware. I found a few that were in all the Jaguars and they never got fixed.

How did the hardware designers react when you pointed this out?

There were only a couple that I’m thinking of right now. One was in a kind of obscure four-color rendering mode. Say you wanted to overlay some graphics, but you’d already used up loads of memory and loads of processing power and all the high-color graphics, and you just wanted to put some text on the screen. But there was a bug in the four-color text overlay thing and it wouldn’t always put the right pixel on the screen. I told them about the bug and I gave them some simple proof of concept code. It could’ve been easily fixed, but unfortunately the chip designs were already finalized.

The other one was a pre-fetching issue. At the time we obeyed the rule that you should have all the graphics code in the graphics coprocessor memory, not in the main memory, because there’s lots of problems fetching code from main memory, as well as it being slower. But there was one problem, even in the graphics processor memory where the code was supposed to run, the pre-fetch didn’t quite work in some obscure conditions. It would work if you single-stepped it, but if you ran it at full speed, it wouldn’t. Eventually I worked it out. I had to put a delay in. It’s a bug because the chip should have been able to work out the delay for itself. You could work around it once you understood what it was. And again, I told the guys about it.

I was told at the time there were only six consoles in existence and that it pretty much looked like circuit boards and wires and no shell. Is this true?

No. When we were working on the Jaguar, there were development kits, which meant that in place of the cartridge, you plug this kind of special thing in where the cartridge goes. That had a lot of wires coming out of it, that would go into your computer. So the debugging kit had wires sticking out all over the place, but the Jaguar itself was finalized, and the Jaguar as such didn’t have wires sticking out all over the place. And I don’t think that there were only six in existence. Each game company had one or a couple. The development kits would have been rarer, but obviously there were at least as many development kits as there were games companies. So I don’t know what we’re talking about, but more like 50 than six.

I think you already answered this a little bit, but would you mind talking a bit more about the first reactions to the demo when Atari saw it?

They were really happy. The development of AvP started between when Wolfenstein came out and when Doom came out. So I was thinking we could probably do something a bit like Wolfenstein on this hardware, which is texture mapped, and it looks 3D, but the movement you can do is more limited than in modern 3D games, right? You’re moving around in a world like a maze, and I came up with the way the doors slide up and down, but they can have cutouts, they can be a certain shape, and then the door within that shape, which isn’t necessarily square, can move up and down. So I thought, well, I could add that bit to Wolfenstein, that would be cool. And it looked pretty nice.

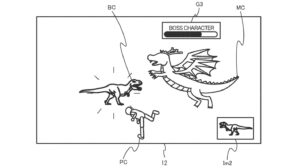

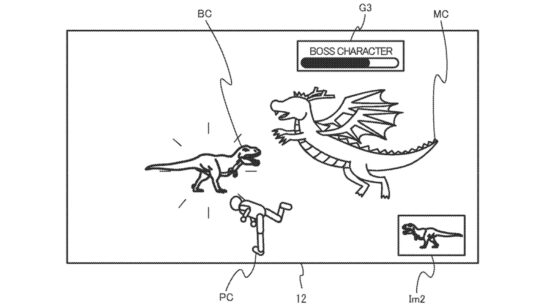

What about the iconic artwork? The maps and characters looked amazing for its time. How was it done?

There are various stories about exactly what happened. But basically, Jason Kingsley, who isn’t credited as one of the artists on the game, was one of the directors of Rebellion. Earlier, when it was just him and his brother Chris, he was more the artist, and Chris was the programmer. At a certain point, Jason said, ‘you know, let’s just go out and buy some Alien and Predator and Facehugger models.’ So they went to some sci-fi store, probably in London, and they bought these great, expensive Facehugger models and stuff that anyone could buy. We had the license to use the characters anyway. And then they were photographing it.

I heard that movie props from Alien were used and that AvP was the first game to digitize photographs into a game?

We didn’t have access to props from movies. They were stuff anyone could have gone and bought, but not everyone would’ve had a license to use them. We had a license via Atari to use the characters and…

But did anyone make a phone call and ask if you could use models that weren’t necessarily the official ones?

Was there an actual phone call about, ‘can we use this particular product that’s made by this company’ and use that character? I’m not sure. Maybe, but it doesn’t matter. We were licensed to use the characters, and so were the companies that made those figures and models. I think everyone was happy with it.

In the early days of games development there must have been a lot of tinkering. Is it true that someone taking a bite out of an apple became a sound effect that made it into the game?

I don’t remember that exact thing. Initially there was only me as the programmer, and two or three artists at Rebellion, so they took on board Jason’s approach of building the things for real. So we were building stuff like the interiors of the cafeteria. The pipes on the wall were made of drinking straws and then spray painted, and then photographed. And then later on, when the game was starting to run we took on an extra programmer, Andrew Whittaker.

Most of the game development took place in Sunnyvale, California, so how did it end up being finished in a fellow British programmer’s parents’ house in Hull?

It felt like all we did was walk between the hotel and the Atari offices, and back to the hotel, and back to Atari offices. We were still progressing, but there’s a lot of pressure, an awful lot of pressure. They had a lot of money riding on it, and they needed the game. And at a certain point, I think Whittaker offered that we could go to his parents’ house in Hull and do some programming there without the producers breathing down our necks.

So the change of scenery helped with bringing the game to completion?

The people at Atari were like ‘you guys probably need a trip back to the UK, you need to see your friends and your family. But also, we don’t want the progress on the game to completely stop.’ So we went to Andrew’s house, and his parents were very, you know, what’s the word, very welcoming. And that did help. I sat in the spare bedroom and carried on programming. I was trying to get the overlays working then, you know, the different Predator vision modes.

Did you have any long marathon sessions towards the end to get it all done?

I think I was kind of finishing off the overlays for the Alien; some aspect about the transparency, or something about the way the game engine would work. And I think, like, basically, if I hadn’t got it done, Atari wouldn’t have waited for it. So I was like, I’m gonna just pull a long session and do this. And that ended up being 72 hours of programming without sleeping. Andrew’s mom coming and feeding me meals, but not sleeping, just program, program, program. So I got the Alien’s heads up display working the way I wanted, and I’m pleased because it worked well in the game.

How involved was Leonard Tramiel (former Vice President of Software for Atari) in the AvP project?

If you were doing anything technical, and you were in the Atari offices, he definitely wanted to be involved. And he wanted to see what was going on. He wanted to have an opinion, you know, so he was obviously quite a technical guy. He understood what he was talking about, but he definitely was also very keen on having an opinion and making sure that you listen to him. I wouldn’t say he kind of changed how any of the games were. Maybe he did a bit. But he certainly wanted to be involved.

Atari was a household name in the US in the late 70s and early 80s before the industry crash in 1983. It wasn’t until the Atari Jaguar came out in 1993, marketed as the world’s first 64-bit console, that the company made it back on the map. Then AvP was released in 1994 to critical acclaim, but sales weren’t that good compared to Nintendo and Sega games. So what happened to Atari?

There was that whole question about why Atari didn’t put loads of money into games. And I just thought at the time that they just don’t understand it. Because, you know, a console sells on its games, right? I think they were kind of lucky to get a game as good as Alien vs Predator. The budget didn’t deserve the game that’s been as well respected as that. They just were kind of lucky that the right people came together. You know, maybe I was the right programmer. Jason made the right decision about how the art team should go about their job, you know, and the right people came together. The Atari programmers like Mike Pooler and the guys at Atari did a great job on the sound. So it just came together as a good game.

If they had this great game and team of people, why didn’t they invest more into it?

The question of why they didn’t put enough money into games, I was like, well, they’re just tight. They just didn’t understand it. Boris Kretzinger wrote a book about the Atari Jaguar, which only came out about two or three years ago on the 30th anniversary of the Jaguar coming out. I don’t remember exactly who, but somebody that he interviewed in that book said that he thought that it was their experience with home computers that came first. So they brought out the Atari ST, and Tramiel was very closely involved in that, and with the ST, they thought that if you get the hardware right, then the software follows. Then you don’t have to sell games, you just sell STs to everybody. That was correct for the ST, and I think the suggestion there was that then they had the same idea about the Jaguar.

There wasn’t enough interest from third-party companies to develop games for the Jaguar?

You have to be a registered developer to get a development kit. So where are the games going to come from unless you sign up good developers to produce games? Like, you can’t just say ‘we’ve got great hardware here, so it’s going to be a success’. And I think it was great hardware. I think it could have achieved far more if they’d put more money into games for it at the start. I think all games companies, all console companies like Xbox or Nintendo, Sony, whatever, any successful console, I think it’s clear to almost all of them, if it’s going to sell it needs to have some killer games when it comes out, and it needs to have a continuous supply of good games. That’s how consoles sell.

You’re from the old school so you must have met some legends in the field. I heard that you hung out with Jeff Minter, for example.

I went to the PC World show in London when I was like 11 or something to walk around all the stands and see the latest computers. And there was Jeff Minter, who was probably, I don’t know what then, but maybe kind of 19, 20 already. And he was like this legend producing these cool games. Later on he did Tempest 2000 for the Jaguar, which is one of the other games that was really good for it. So he was there at a certain point while I was at Atari, he was there and, you know, we got to hang out, I think, with a couple of the Atari producers. And we kind of all drove up to some kind of creek up in the mountains above Mountain View and kind of hung out and possibly smoked some nefarious substances with Jeff Minter. So that was pretty awesome.

The community of game developers must have been small in the UK back then?

I don’t think it was that small by then. I mean, there were lots of companies. There was Rare, Argonaut, Ocean Software, lots of them. And then it would depend if you were running the businesses. I’m sure the heads of all the companies knew each other. As a mere programmer, I would have known all the people I’d developed games with and known all the people at the companies I’d worked at. But I wouldn’t have necessarily gone out and hung out with the bosses of all the other companies either.

What’s the last game you worked on?

Blimey, good question. I think it was Formula Karts. Yeah, so before Atari, when I was younger I used to publish games listings in computer magazines, and also write games that everyone played on the computers at school. My first paid role was on an early PC 3D game, Xiphos. After that I worked at Argonaut and did flight dynamics for a Microprose game called ATAC. Then, after Atari, I went to Manic Media and worked on Manic Karts and then Formula Karts. Formula Karts was at the very, very end of when the graphics engines for PC games were entirely still running on the CPU, because there weren’t GPUs, and there certainly wasn’t OpenGL.

So everything had to be built from scratch every time?

You wrote the graphics engine from scratch. But if you wanted texture mapped polygons on the screen, there wasn’t a GPU that you could tell to go and texture the polygons. You had to work out some tightly optimized assembler code and the loops yourself to put the texture in the right places. I knew in theory that there was a clever way that you could texture because logically, if you’re doing a perspective texture map, every single pixel requires a division or rather two divisions to find the right texture. But you can shortcut that, because once you’ve got the correct texture for the first pixel, the next one can be correctly calculated using just some adds and subtracts starting from those first divisions. So once I knew this was possible, I sat down with a pen and paper for two or three days and actually worked out how to do it for myself. That’s much better than just reading it up in some book.

It sounds like you are clearly passionate about these things.

Yeah, I mean, it’s interesting. It’s fun stuff to work on.

So what made you leave the gaming industry?

That is a good question. The thing is, the games industry is a very kind of a flat career structure. There’re more roles now, but if you’ve worked on the 3D graphics engine for some hit games, then your next job will be working on the 3D graphics engine for other hit games, followed by a job where you’d be working on the 3D graphics engine on some other hit game for another company. You get paid fine, but obviously, I wasn’t on royalties. So the salary was fine for my age at the time, but I didn’t make some huge amount of cash because Alien vs Predator was successful. I was always on the technical side and probably never going to go and set up a company and make the big bucks.

You don’t miss it? You don’t miss the 72-hour stints with frozen lasagna from the microwave?

I wouldn’t say that I miss it. I’d probably say that I’ve had the odd 72-hour stint on other things. I did a PhD about Philosophy of Cognitive Science and probably did a couple of 72-hour stints finishing that. And more recently I’ve become a contributor to some pretty cool open source software called OpenCore which lets you run macOS in places where Apple never necessarily intended it to be run. So there’s more to life than just games, important as they are!